Feature by Grandmaster Suck

We decided to republish this article about Dr Adam Little on our new site.

We first made contact with him in the run up to the tribute dinner held in 2006 to mark the 50 years since Bill Struth had passed away. Dr Little would be a guest that night and he had a ball – he was stunned to have people asked him to sign shirts, programmes and other memorabilia – a very humble man he phoned me the morning after the dinner to thank the organisers and you could tell he was still on a high.

He sadly passed away in 2008 but his part of the Rangers story provides a valuable insight into the club’s history.

Adam Little had a fascinating career playing for Rangers, Scotland (wartime caps), Arsenal and Morton after being signed as a youth by Mr Struth.

Born on the 1st of September 1919 Dr. Little remains sprightly and independent living on his own despite some eyesight problems. His sight may be impaired but his memories and wit are as sharp as ever with many an anecdote being being told with a hearty chuckle.

After many years of practice in Port Glasgow he retired to rural Renfrewshire.

I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Little this summer along with Bob McElroy, the editor of the Rangers Historian and veteran Bluenose John Dykes who actually saw Dr. Little play during wartime. More articles will appear in future editions of FF and the Historian but I thought that with the 50th Anniversary of Mr Struth’s death being upon us and Dr. Little being a guest at the commemorative dinner at Ibrox on Friday this might be an apt time to publish some of his recollections.

Adam Little was born in Blantyre and retains a great affection for his birthplace despite moving to Glasgow when his father moved from working in the mines to joinery and then work as a caretaker in a school in Rutherglen. He refers to Glasgow as “God’s Own City.”

Football was the only sport for him – he played for Eastfield School; then Rutherglen Academy; before playing for the Lanarkshire select team and then gaining a schoolboys international cap.

His brother Gilbert, ten years his senior was also a talented player but despite a trial for Airdrie would never play professionally. Instead he went on to complete an honours degree in civil engineering and then aeronautics. By a curious quirk of fate he worked on the design of the wings of the Wellington bomber despite being a conscientious objector – he resigned from the project on discovering the wings were for a bomber and instead took up a job with the London Metropolitan Water Board.

He was to cross paths with Celtic a few times on an off the field. He was offered a contact by them but his father (who as a great Rangers man took little convincing!) rejected it because of the flippant attitude displayed by the then manager. However, former Celtic player Nap McMenemy (Jimmy “Napoleon” McMenemy) played a hand in the former Rangers’ formative years – he ran an after schools football team in the district which had the nickname of the “Rutherglen Midgets” due to the small stature of the squad which played matches all over Glasgow.

At 17, however, he signed for Rangers. His schools team always attracted a decent crowd when playing at Stonelaw Road and during one game he noticed that when the ball went out in one part of the field a spectator would turn away from the players. That would prove to be Mr Struth on a scouting mission.

The next morning there was a knock on the door of the family home. It was Struth. He chatted with family and Adam. ‘He asked what I intended to do with myself – I said sit my Highers and hope to study medicine.’ ‘Excellent’ said Struth ‘we always like to have a doctor in the club.’

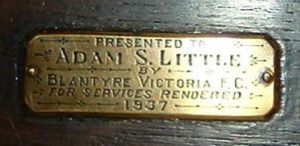

He signed for Rangers and started to train at Ibrox. However, Struth farmed him out to play for Blantyre Vics – a club his father chose for him because of the family connections with Blantyre. He continued at school; at the weekends he played for the school in the morning and the Vics in the afternoon.

When he left the Vics they offered him a choice of farewell presents – either a radio or a writing desk. His father said – “the radio will only last for a couple of years – the desk will last forever.” He was right – Dr. Little still has the desk and it’s inscribed plaque in his home.

Life was good for the young medial student – he trained twice a week at Ibrox, played at the weekend and studied at Anderson’s Medical College – part of Glasgow University. “I was earning more in expenses with Rangers than my father made as a wage.” He’s grateful to football for enabling him to get through university without being too much of a burden on his family – and having two sons graduate from the one working-class family in those days was no mean feat.

Footballers weave in and out of Dr. Little life – his old team mate Dave Kinnear scored a goal in the famous game in January 1939 when 118,567 saw Rangers beat Celtic 2-1. Dave’s son was a joiner and examples of his work are in Dr. Little’s home.

He remained friendly with Celtic’s John McPhail whom he’d played against in a Schools Shield Final which St Mungo’s won 2-1 against Rutherglen.

Of pals at school – Archie Baird played for Aberdeen and Alex Crossley for Queen’s Park.

Slowly he began to make his way into the first team – two League appearances in 37-38 became four in 38-39. And then the war came.

Being a medical student meant he was in a reserved profession. Willie Waddell who had sat Highers with Adam was due to study dentistry but that was not a reserved profession so instead he ended up working in a shipyard. The war, university and a year’s practical in a war hospital saw his Ibrox career rise as more established players joined the Forces. It was not to last however as he was posted to Egypt.

During the war he played several times for Arsenal when stationed down south. In Egypt he was assigned to GHQ Cairo and was quickly given a place in a British Army football team bristling with stars which played to entertain the troops and often meant last minute dashes by aircraft intervening in hospital work. Egypt, Tunisia and Palestine were all visited.

Adam made his first team debut in October 1937 playing Stoke City in the famous Holditch Colliery Disaster Relief match from which Rangers got the famous Loving Cup used toast in the New Year at Ibrox.

“The Headmaster called me out of class and told me “Mr Struth wants you at Ibrox.” George Brown was a schoolteacher and could get off so it was a great treat for me to play against Stanley Matthews.”

“We got a whole host of gifts – all china.” But no money. “Mr Struth asked us to donate our week’s wages for the fund and everyone did.”

His League debut was at Arbroath – “a hellhole!”

Adam played twice in the same Rangers team as Stanley Matthews when he guested during the war. Could the great man have signed for Rangers considering the affection he often talked of them with in later years? Dr. Little doesn’t think so. Matthews knew his worth – ‘clubs were making a fortune from his name’ and with a chuckle “he liked the coppers!”

AT UNI, AT WAR AND AT IBROX

Adam trained Tuesday and Thursdays at Ibrox when studying. Struth encouraged him in both sport and education “something every boy should do – combine both.”

No-one at Ibrox was a pro during the war – pre-War players were at work in the yards, in university or away in the forces. Struth himself acted as a masseur and physio to disabled soldiers housed in the nearby Bellahouston Hospital and threw the doors of Ibrox open to those servicemen who wanted to use the gymnasium.

The war years were eventful for Adam in sporting as well as education terms. He played in the 1942 Southern League Cup Final against Morton – Rangers winning 2-1. Against men such as Billy Steele, Johnny Kelly – known as Fingers because two were blown off in a pit accident and his pal Tommy Orr.

STRUTH STRAIGHT AS A DIE

Tommy Orr is recalled with great affection both on an off the field – theybecame great friends and used to bring in New Year together.

Mr Struth was interested in signing Tommy and asked Adam about his background and his attitude. Spurs were also in for him but he held off when Adam told him of Rangers interest. However, things were to go wrong.

During signing talks the Morton representative asked for a cut of the transfer fee. ‘Struth threw him out and the transfer was over. Tommy more or less gave up after that – it ruined Tommy’s career.’

Tommy’s son Neil played for Morton, Hibs and West Ham. Adam has great memories playing cards with the youngster – ‘we both cheated!’ he laughs.

John Greig was interested in signing Neil Orr but Morton wanted too much money.

PLAYING THE RANGERS WAY

Adam played wing half – but could also play outside left. Indeed he fondly remembers the famous journalist “Rex” giving him praise for that position in a Cup Final against Dundee United “He said I didn’t kick the ball – I creamed it.”

“Playing for Rangers was easy – you were surrounded by good players and they helped you play. You were weaned in the method of play.”

Struth was at the top of the club but day to day fitness was in the hands of the trainers. On the field of play tactics were handed down by the captain – he was “absolutely crucial” – and the senior players who told you how to play “The Rangers Way.”

“It was more the spirit of the club that the captain instilled. You couldn’t tell a bloke how to play football in those days because that was all you did so it was natural talent that came to the top and so it was case of getting the players mentally together and dovetailing them together.”

Playing The Rangers Way – was “handed down from generation to generation. You were introduced to a system and the first team players told you what to do. If you didn’t you wouldn’t last long.”

ALWAYS LOOKING TO ATTACK

“At Ibrox we swung on the pivot of the centre half. Left half tracks back – the right half went forward – the same thing happened up front – of the left side went back the right side was up.”

Simple things were drummed in – throw-ins should always be used to pressure the opposition – “no-one can be offside at a throw-in.”

STRUTH AS TACTICIAN AND MOTIVATOR

I asked Dr. Little to try and explain the magic of Struth. For instance – we are told that there were no tactics in those days and no team talks – but when you are training a full-time squad of athletes and playing in front of vast crowds in professional sport there obviously had to be tactics!

Also, with Struth’s background in athletics and interest in the mechanics of sport were, in Dr. Little’s opinion as a medical man, Struth’s training routines effective?

“Absolutely, he was way ahead of his time. And in psychology he was a wizard – he controlled the team. You’ve eleven players and no two are alike – he could handle each and every one of us. He knew our weaknesses. He was strict – you have to live by his standards and if you didn’t you were out the window. If you disobeyed certain things you were just transferred.”

Archie Macaulay – later to be a wartime internationalist and play in the famous Great Britain side in “The Match Of The Century” in 1947 – was “out on the skip on the Thursday night” – the next week he was transferred to West Ham the following week, no questions asked.

Dr. Little reckons Struth’s obsession about how the players dressed and behaved themselves was a deliberate strategy to improve them as players. By making them pay attention to details of appearance he got them to think about their bodies – to never make do with 2nd class or poor effort on or off the pitch.

Adam found himself once pulled up in the manager’s office for knotting his cravat the wrong way! “Struth was such a psychologist he went to great lengths to cultivate this attitude. You could be combing you hair in the mirror and he’d ask “is sixpence too much?” – wee tough boys put up their collars, Rangers players wore their clothes properly.”

“For an example – there was a bath the size of this room – if you came out of the bath in front of a first team player the trainers would ignore you and go to the first team player to give him a rub down.” the first team players got the best of everything.

Weather permitting, training at Ibrox started with a brisk mile’s walk around the track in shirt sleeves with Struth’s expert athletic eye – he had been a professional sprinter – watching for faults in gait or step.

NO DRESSING ROOM RANTS

Mr Struth never gave a pep talk before a game – but he’d position himself at the tunnel to shake a hand or clap a shoulder as the players went out and leave them with the same last thought that became his mantra – “Every post is the winning post.” What he meant was that every free kick, every restart, every move should be played at full pelt as if it was you last or your only opportunity.

The only time he came into the dressing room was after a dreadful defeat by eight goals to Hibs. The dressing room was silent and the players thought they were going to get what for, instead Struth simply said “God help the team you’ll be playing next week.”

THREE EIGHTS

Dr. Little played in three games with eight goals scored by one team – that famous defeat by Hibs – in a wartime international defeat 8-0 by England at Maine Road and more happily an 8-1 win over Celtic at Ibrox during the war.

He went to the game in the company of a medical student friend – Patrick Cassidy – later to be known as Doctor Wee Cass in the southside of the city and Patrick’s girlfriend Rita.

Adam’s eyes twinkled as he recalled the game – “Rita said to me – we are going to win today and I said Rangers will win by a hat-full and she wouldn’t speak to me after the game!”

Celtic had two players sent off that day but there was no crowd trouble – “There was no animosity – the Celtic crowd drifted off quickly!”

Other Celtic games would not be so friendly but could still produce moments of laughter amidst the mayhem. Adam recalled his first “bottle party” where fans showered the pitch with objects.

Jerry Dawson the Rangers keeper was being having a tussle with Jimmy Delaney and a penalty was awarded in front of the Celtic End. Delaney was lying on the ground pretending to be hurt but as the bottles started to land around him “he was up and in a flash and ran away!” Justice was done and the penalty was missed.

STRUTH’S PRIDE AND JOY

Asked for memories of Mr Struth Adam said the one he has imprinted in his mind is of Struth opening the Ibrox Sports every summer. Tens of thousands came to watch and numerous world records were set at Ibrox – including by Rangers member Eric “Chariots of Fire” Liddle.

He would take to the microphone in the centre circle to announce the start of the day’s events in the strong Scottish summer sun like a peacock strutting it’s feathers – “The Sports were his baby – it was his pride and joy.”

Even his love of good suits and his appearance had a practical side – he had UV tubes at Ibrox which Struth used to top up his tan in the winter but which were also used in rehab for injured players. Martin Bain eat your heart out!

AFTER THE WAR

When he came back from military service Dr. Little found that the war had changed Ibrox as it had changed the country. Players had moved on; rationing and the strain of work had aged Struth; new players had come in; even the style of play had changed.

Football had helped him get an education and helped him see the world – his appearances at Ibrox waned after the war as players had taken his place when he was away so he agreed to transfer to Morton and the Greenock/Port Glasgow part of the world was to be both his place of work and his home for many happy years before retirement.

Loved reading about Dr Little. He and his family were neighbours of ours in Port Glasgow. I didn’t know he was so well known until I read this. Haven’t heard anything about him or his family since I left that area about 1965. So good to read about his earlier life